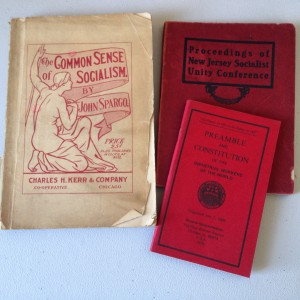

Cataloging the collection at the East Side Freedom Library has exposed all of us to the art involved in the printing world and some of the changes that occurred in that field over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We found after cataloging several boxes of books that we could guess the decade a book was printed in before opening the cover. Book covers and dust jackets serve as a mirror to the era they were created in, reflecting the zeitgeist of their times. G. Thomas Tanselle in “Dust Jackets, Dealers, and Documentation” claims that “Dust jackets constitute one of the most significant classes of printed ephemera and a basic category of evidence for publishing history.”[1] Through the examples available to us at the East Side Freedom Library we can trace some of that history in both book covers and book jackets.

John P. Feather, in The Book in History and the History of the Book, explains that books became available to a wider audience with the innovations that improved the printing process, beginning in 1780.[2] The Enlightenment value placed on literacy met the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution and the nature of book creation changed. The world of leather-bound tooled and gilded covers made way, reluctantly, for cloth covers and paperbacks. Where once wealthy buyers had purchased their books unbound so that artisans could bind them in leather covers that would match the other volumes in the owner’s library, pre-bound books became the order of the day.

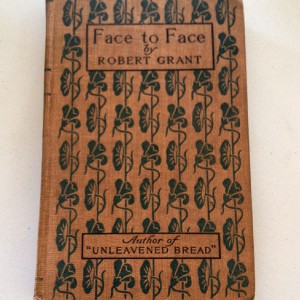

Decoration of pre-bound leather books was a subject of much debate in the late nineteenth century, with various camps making their case for decoration that would, or would not, reflect the subject of the book being covered. Some book artists argued against decoration that would reflect the contents of the book, espousing decoration that was purely decorative. T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, writing in The Studio in 1893, stressed that “a book cover design must not be allegorical or emblematical.”[3] Many of Cobden-Sanderson’s cover designs are floral, a convention popular until around 1909 when it diminished in favor of new motifs.

Ellen Mazur Thomson indicates that along with the technology that supplied a wider audience with books came concerns that popular taste, influenced by advertisers, would be degraded and questions were raised about what the design vocabulary should be for mass-produced books. Early cloth covers carried the same sorts of decoration, the same “design vocabulary,” that leather bound books had displayed. Early cloth bindings were decorated with precise patterns of leaves, flowers and symbols, as not all designers subscribed to Cobden-Sanderson’s boycott of symbolism (in fact he broke his own rule on more than one occasion).

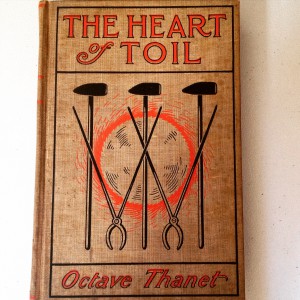

Some graphic artists explored alternative designs. Will Bradley, a graphic designer and book cover artist, suggested that “even trolley cars and golf balls could be reformed, refashioned or in some manner conventionalized into inventive and interesting decoration.”[4] In the ESFL collection the books that best illustrate this early twentieth century change in design direction are Miss. 318 and Miss. 318 and Mr. 37. These stories about Miss 318, a shop clerk, and her beau, Mr. 37, are decorated with the emblems of their occupations; a basket for transporting orders into the stockroom from the sales floor in Miss. 318’s case and the fire hose and badge emblems for Mr. 37. Not only is this a departure from the once popular floral forms, but in the working class heroine and hero of the books, a wider, less elite audience is implied. Feather indicates

We can see printing as only one of many trades that were transformed by new equipment and new techniques. At the same time, we can see it responding to society’s needs and demands, not only economically, but also in the cultural and political spheres.[5]

Books were becoming less of a luxury for the wealthy and more a commodity available to an audience that crossed class lines.

In an effort to appeal to a wider audience, publishers began to make use of images on covers that were more likely to draw the interest of the bookshop browser. Thomson explains that “publishers, who viewed the cover as an advertising tool, were advocates of illustration that they believed promoted sales. The practice of gluing chromolithographic images onto cloth bindings encouraged this style.”[6] Two copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the ESFL collection, both undated, show on the one hand a generic floral cover and on the other a cover with some floral motifs, but used to offset an oval photographic image representing the title character that has been glued onto the binding.

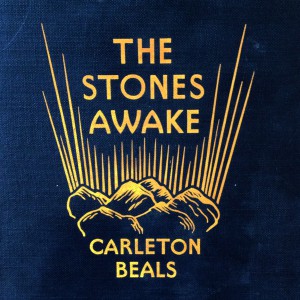

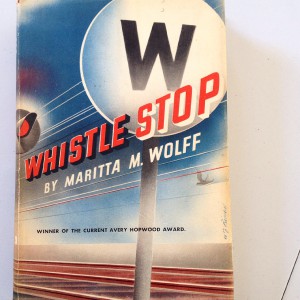

Dust jackets were also undergoing a transformation. Tanselle created a timeline that traced this evolution from the simple printed wrapper that covered the book entirely in the 1830’s, to the jackets with flaps, originating in the 1890’s, which carried the same design as the book beneath. By the 1920’s bindings had become less decorative with the printed jackets as the focus. Jackets were less expensive to produce than decorated bindings which now carried a simplified design, or were not decorated at all, while the jacket carried not only art work but story teasers and advertising for other titles offered by the publisher. Tanselle explains that “from then on the history of book jackets is primarily the story of shifting tastes in graphic design and in advertising style, rather than changes in form or function.”[7] One of the advantages to a publisher of dust jackets was that it gave the publisher the ability to put a new jacket with a fresh design on a book to stimulate sales on older stock, and update the advertising to promote current offerings.

Book design is not a primary focus of the ESFL, nor of the scholars whose collections make up the library, but when the collections blend together they become more than the sum of their parts. Book design is just one of countless research opportunities that present themselves when you browse through the shelves…and I hope you will. The covers of the books referenced in this post can be found, along with many others, in Photo Gallery – Book Covers.

[1] Tanselle, G. Thomas. Dust Jackets, Dealers, and Documentation. 46.

[2] Feather, John P. The Book in History and the History of the Book. 17.

[3] Thomson, Ellen Mazur. Aesthetic Issues in Book Cover Design, 1880-1910. 38.

[4] Thomson, Ellen Mazur. Aesthetic Issues in Book Cover Design, 1880-1910.242.

[5] Feather, John P. The Book in History and the History of the Book. 18.

[6] Thomson, Ellen Mazur. Aesthetic Issues in Book Cover Design, 1880-1910.233.

[7] Tanselle, G. Thomas. Dust Jackets, Dealers, and Documentation. 89.

![IMG_6772[1]](https://esflpastandfuture.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/img_67721.jpg?w=300&h=300)

home of a growing collection of literature on the labor movement and power of the working-class, is housed in a building essentially given life by Andrew Carnegie. Industrialist, philanthropist, and, oh yeah, the guy who put Henry Frick in charge of dealing with the Homestead Strike of 1892 that eventually ended in a broken Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union and nine dead workers.

home of a growing collection of literature on the labor movement and power of the working-class, is housed in a building essentially given life by Andrew Carnegie. Industrialist, philanthropist, and, oh yeah, the guy who put Henry Frick in charge of dealing with the Homestead Strike of 1892 that eventually ended in a broken Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union and nine dead workers.![IMG_5673[1]](https://esflpastandfuture.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/img_56731.jpg?w=300&h=300)

![IMG_5674[1]](https://esflpastandfuture.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/img_56741.jpg?w=300&h=300)